|

1. Overview: Regional Dialects in the German-speaking Countries Up until now we’ve used Standard German as the basis for our discussion of the German language. This is because as foreign language learners, you need to know the particular variety that will enable you to communicate MOST efficiently and effectively! However, when you actually travel to the German-speaking countries, you’ll soon realize that there are a LOT of regional varieties – or dialects – of German. Dialects are characterized not only by pronunciation, but also by grammar and vocabulary. The dialects of the German-speaking countries are traditionally grouped into three categories: (1) Niederdeutsch; (2) Mitteldeutsch; and (3) Oberdeutsch.

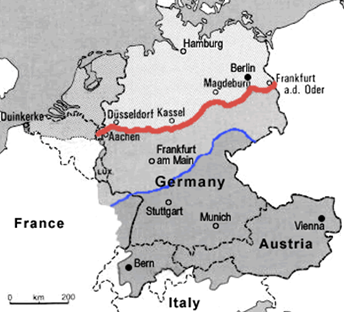

No, that’s not a typo – the Low German dialects are actually found in northern Germany while the Upper German dialects are found in southern Germany, Austria, and Switzerland! This may seem confusing, but just remember that the terms Low German and Upper German refer to the topography (i.e., elevation) of the regions where they are spoken. The Low German dialects are spoken in the low coastal regions bordering the North Sea and in the flat plains regions of northern Germany (above the red line, or the lightest grey area on the map). The Upper German dialects are spoken in the mountainous regions of the Bavarian Alps in southern Germany as well as in the Austrian and Swiss Alps (below the blue line, or the darkest grey area on the map). The Central German dialects are spoken in the regions in between (between the red and blue lines, the medium grey area on the map). The Benrath Line (the thick line to the north) separates the Low German dialects from the Central German dialects, and the Germersheim Line (the thin line to the south) separates the Central German dialects from the Upper German dialects. Source: http://www.aboutaustria.org/german_language_2.htm 2. The High German Sound Shift

The High German Sound Shift was already outlined in the last chapter (Kapitel 6) so we won't go into too much detail describing it here. You should know, however, that the differences it describes are not only between German and English, but also between the Southern and North-German dialects. The High German sound shift affected the Upper German dialects and, to a lesser extent, the Central German dialects. (Think of the area where the Central German dialects are spoken as a kind of in-between zone – most, but not all, of the sound shift took place here.) Since these particular dialects eventually formed the foundation for a standardized German language (i.e., High German), the shift is known as the High German sound shift. What about the Low German dialects? Yep, you guessed it – the shift did not affect them. Nor did it affect other Germanic languages like Dutch and English. Take a look at the chart below. You’ll notice that the sounds of certain Low German words are the same as Dutch and English words!

You may find another dialectal sound shift not indicated in the above chart. When you travel from Northern Germany to Southern Switzerland you notice that in Switzerland the initial K is very often pronounced as ch. So, instead of saying Knie (knee) the Swiss say Chnü or instead of Kind (child) they say Chind. 3. Plattdeutsch, Berlinerisch, Kölsch, Bayrisch In the following sections we will look at four dialects in Germany. These are definitely not the only ones but perhaps they are the most famous ones. For each dialect we provide a short overview of the pronunciation and a list of words compared to the Standard German equivalent. Each dialect in the next three chapters also has an Asterix cartoon illustrating the particular dialect. You will also find a link to the web page where the cartoon is taken from, in case you want more information. See if you can find some features listed under each dialect in the Asterix cartoon. PLATTDEUTSCH Plattdeutsch (also: Niedersächsisch) is a group of dialects spoken in the state of Lower Saxony, the word platt meaning flat in the sense of either elevation or manner of speaking. These dialects did not take part in the High German sound shift that altered the consonants p, t, k, etc., so they are deemed Low German.

BERLINERISCH Berlinerisch is spoken in and around Germany's capital city. The city's location on the Benrath Line has lent the dialect its (mainly) Low German phonological features (i.e., ich ick and Apfel Appel), while its many immigrants have introduced vocabulary into the dialect from French and Turkish, for example.

KÖLSCH Kölsch is spoken in and around Cologne, in the western German state of North Rhein-Westphalia. Cologne lies just south of the Benrath Line that separates the Low German dialects from the Middle German dialects. Thus, while Kölsch shares some phonological features with Berlinerisch, for example, it is really a Middle German dialect. Kölsch is well known for sounding nasal and sing-songy, two qualities which stem in part from its contact with the French language during Napoleon Bonaparte's 21-year-long occupation of Cologne.

BAIRISCH Bairisch is a group of dialects spoken in the southernmost German state of Bavaria. (The word Bayerisch refers to the political territory of Bavaria. In the late 1800s, Bavarian King Ludwig I insisted on retaining the Greek y in the spelling of his beloved territory.) The High German sound shift was entirely realized here.

|